In 1643 a Bishop called Brynjolf Sveinsson was given forty- five pieces of vellum containing poetry and prose from the heart of ancient Northern European indigenous culture. This collection is called The King’s Book (the Codex Regius in Latin). It is thought to have been written around 1270. Between 1270 and 1643 the manuscript was hidden from public view, presumably to protect it from being destroyed by the new religion which arose from Rome. Who the family was that protected this manuscript for over three hundred years we don’t know, and nor do we know their tradition, but we can be sure that it would have been a treacherous secret to bear safely through the medieval centuries. The Bishop did not himself keep the manuscript; instead, he offered the collection as a gift to the King of Denmark. There it remained in Copenhagen until 1971, when it was returned to Iceland.

Codex Regius (The King’s book) of Eddaic Poems and Flateyjarbok (Wikimedia Commons)

Warships had to transport the manuscript across the sea, as a plane journey was seen as too risky – such was the preciousness of the papers. It is not surprising: these vellum papers represent the few written remains of our indigenous past of Northern Europe.

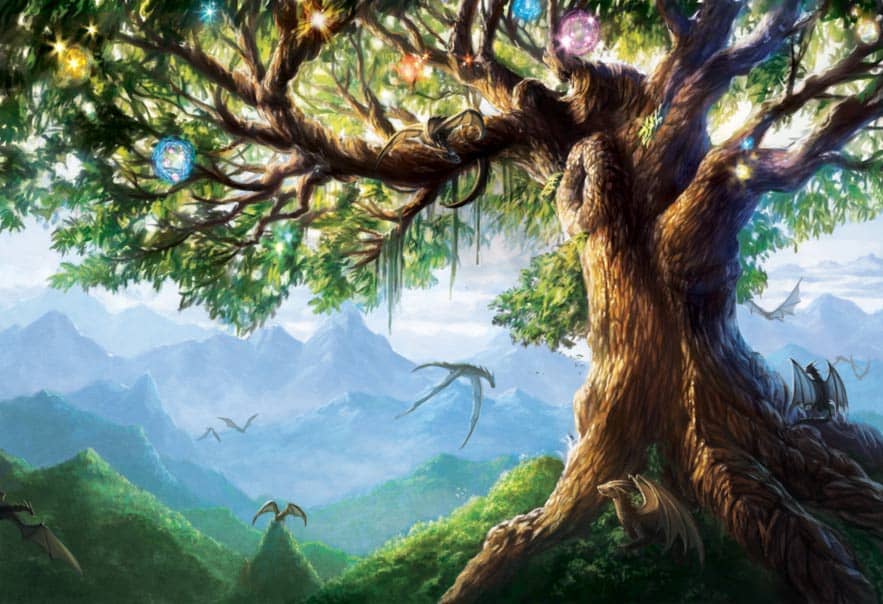

When we open these old scripts we find at the heart of the Norse mythology contained within a symbol as archaic as campfire: the World Tree, Yggdrasil.

I know that an ash-tree stands called Yggdrasil,

a high tree, soaked with shining loam;

from there comes the dews which fall in the valley, ever green, it stands over the well of fate.

(Seeress’s Prophecy)

The most satisfactory translation of the name Yggdrasil is ‘Odin’s Horse’. Ygg is another name for Odin, and drasill means ‘horse’. However, drasill also means ‘walker’, or ‘pioneer’. Some scholars would argue that the name means ‘Odinwalker’. In some parts of the manuscript, Yggdrasil and Odin seem to be one and the same.

When Odin hung, speared, for nine days on the World Tree, he uttered the words that he had ‘sacrificed himself onto himself’. This stanza gives us a description of the unity existing between the Godhead and the Tree in the myths. To emphasise this connection, we find in old English the word treow, which means both tree and truth. Etymologically, then, truth and tree grow out of the same root. Subsequently, in the Norse creation myth, man and woman originated from trees. We are all the sons and daughters of the Ash and Elm tree: the first man was called Ask, born from the Ash, and the first woman Embla, born from the Elm. Their oxygen offers us the primordial conditions for life. Ask and Embla sprouted from Yggdrasil’s acorns, and so it is that every human being springs from the fruit of Yggdrasil, then to be collected by two storks ,who bring them to their longing mothers-to-be. In Scandinavian folklore, they say that children are born through the knot holes in the trunks of pine trees, which is another version of the same myth.

Odin creates Ask and Embla. Published in Gjellerup, Karl (1895). ‘Den ældre Eddas Gudesange’. (Wikimedia Commons)

Artur Lundkvist is one of Swedish literature’s greatest tree worshippers. Following a reflection on trees and forests, he writes:

‘… in every human there is a tree, and in every tree there is a human, I feel this, the tree wonders inside a human being, and the human being is caught in the tree … I serenade the forests, the forest sea is the second sea on earth, the sea in which man wanders. The forests work in silence, fulfilling nature’s mighty work; working with the winds, cleaning the air, mitigating the climate, forming soil, preserving all our essentials without wearing them out.’

The people represented Yggdrasil by planting what was called a ‘care-tree’, or ‘guardian tree’, in the centre of the homestead. It was a miniature version of Yggdrasil, and a stately landmark in the courtyard. The care-tree was a figurative expression of the interdependence of the world around us. It had a soul which followed the lives of those who grew up under its shadow and boughs. If the care-tree had witnessed many families growing up, the relationship between the tree and the family would have strengthened; this relationship was known to be private and confidential within the family line. Many such care-trees can still be seen in Scandinavia. I would argue that this is the origin of the Christmas tree. We unknowingly bring the World Tree into our home every winter solstice.

The Yggdrasil from Prose Edda, 1847. Painted by Oluf Olufsen Bagge (Wikimedia Commons)

Read the rest of the article at AncientOrigins